Rail transportation along the Central Corridor is run by Tanzania Railways Limited (TRL). The company had been operated under a concession between RITES of India and the Government of Tanzania since 2007, but the concession was canceled in 2011 due to labor conflicts and financial distress brought about by falling traffic flows. The TRL system is composed of over 2,700 km of one meter gauge track capable of supporting 15 ton/axle loads. Speed restrictions of 13–50 km/hr are in place on many sections of the track due to their poor condition. Given these speed restrictions, train turnaround is estimated at about 18 days from Dar es Salaam to Mwanza or Kigoma, instead of the scheduled 10 days. In the past five years, TRL traffic has declined, falling 30 percent from previous levels. This decline can be partially explained by a lack of investment in new infrastructure, leading to unreliable service that has driven customers to use road transport instead of rail.

In 2009, less than 6 percent of Central Corridor traffic moved by rail. Rail transport via the TRL does not technically connect the Port of Dar es Salaam to any other country in the EAC. Instead, cargo is distributed through an integrated rail/ferry system, traveling on rail through Tanzania to the port of Kigoma on Lake Tanganyika (connecting to Bujumbura, Burundi, and to Kalemie and Uvira, DRC) or to the port of Mwanza on Lake Victoria (connecting to Kisumu, Kenya, and Port Bell, Uganda). The merchant fleet operating on Lake Victoria is reportedly more modern than that of Lake Tanganyika, but public rail and port intermodal facilities are outdated. There is no working cargo equipment at Kisumu or Port Bell, such that containers are handled only if they come in on a rail wagon. The rail/ferry network on Lake Victoria is in such a state of disrepair that most cargo is transported by road around the lake. The major difference in delivery time can be explained by poor rail infrastructure at the Port of Dar es Salaam, as well as poor intermodal transfer infrastructure at the rail/lake port. These multimodal routes were more frequently used in the past, and rehabilitating the rail system could make them more competitive in the future.

Tanzania has two railway systems: A central line extends towards Kigoma and Mwanza on Lakes Tanganyika and Victoria respectively, and is run by Tanzania Railways Limited (“TRL”) with assets in the ownership of the Railways Assets Holding Company (“RAHCO”), and a southern route extends from Dar es Salaam into Zambia, operated by the Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority (“TAZARA”).

Both TRL and TAZARA are in dire need of investments to improve their infrastructure. The northern and central railway was built at the turn of the century, and is of 1,000 mm gauge, and is of roughly 2,700 km in length[1]. The railway suffers from repeated washouts and, just like TAZARA’s rail line, is short of serviceable locomotives. The railway links the port of Dar es Salaam to Mwanza on Lake Victoria, providing part of a multi-modal link over the lake to Uganda. However, by the time the TTFA survey team visited in November 2013, no cargo had been delivered by Rail in 3 months. This is a confirmation that the currently Rail services to mainly Uganda via Lake Victoria is not reliable.

The demand for rail in general declines as a road network expands, as has been the case with Tanzania. The advantage of rail over roads lies in fuel costs and the ability to carry large tonnages of bulk freight far distances. In addition, overloaded trucks cause accelerated road wear, making rail seem like the logical alternative from a policy point of view.

However, two factors play against the demand for rail: Unless a rail station is at the final destination or the original origin of what is being shipped, rail is inevitably multi-modal and requires goods to go through a modal shift (usually roads, or, as was the case in Mwanza, ferries). In addition, road transport allows for considerably more flexible scheduling of the beginning of a shipment, and for better information on the progress of the shipment.

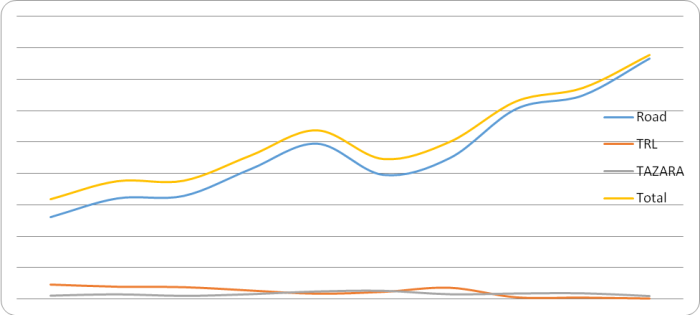

Source: Analysis by the study team

Figure 3-7: Analysis of Traffic distribution between Road & Rail

The port has witnessed consistent decline in cargo transported by rail over the past 10 years from 17.4% of overall cargo in 2013 to 1.3% in 2012. This has been one of the contributing factors to the high dwell times at the Dar port.

The backbone of the Central Corridor is the Central Rail Line that runs between Dar es Salaam and Kigoma in western Tanzania and to Mwanza in the Northern Tanzania. While this railway was designed to handle 5 million metric tons of cargo per year, it currently only carries less than 2 percent of its capacity.

Projects are underway to overhaul the current central line. Countries such as China and Japan have offered support and funding to refurbish the railroads and purchase new locomotives and carriages, although much of the total investments required to completely renovating the existing railway network, an estimated $1 billion — has not been secured yet.

In the short term, transport along the Central Corridor could benefit from upgrades to the railroad, while in the medium term it could benefit most from the use of more trains. In the long term, however, Tanzania may be required to convert its current meter gauge (1,000 millimeters) railways to the standard gauge (1,435 millimeters), which could handle a larger capacity. Such a conversion, which would require the construction of a completely new railroad, cannot be completed in the short term because Tanzania cannot suspend railway operations and because the country’s existing railroad bridges cannot accommodate the wider gauge.